The idea of having a “job” – showing up at a specific workplace, for set hours, doing specialized tasks in exchange for wages – seems so natural to us today that we rarely question its origins. Yet this arrangement, which dominates modern life, is actually a relatively recent invention. For the vast majority of human history, people lived and worked in fundamentally different ways, sustained by patterns of life that had endured for millennia before being swept away by the Industrial Revolution.

Life Before the Industrial Age: The Rhythm of Subsistence

To understand how revolutionary the concept of the modern job really is, we need to step back and examine how people lived and sustained themselves for thousands of years before the late 18th century. The pre-industrial world was fundamentally organized around subsistence – the practice of producing just enough to meet one’s immediate needs, with little surplus for trade or accumulation.

In this world, the overwhelming majority of people lived in small agricultural communities. Families typically owned or worked small plots of land where they grew their own food, raised animals, and produced most of what they needed to survive. A typical peasant family might grow grains and vegetables, keep a few chickens or a pig, maintain a small garden, and perhaps have access to common lands for grazing animals or gathering firewood.

The work was seasonal and cyclical, following the natural rhythms of agriculture. Spring brought planting, summer meant tending crops, autumn demanded harvesting, and winter was a time for indoor crafts, equipment repair, and preparation for the next growing season. Unlike our modern eight-hour workdays, labor was distributed unevenly throughout the year, with periods of intense activity during planting and harvest times, and slower periods during winter months.

The Barter Economy and Community Self-Sufficiency

Perhaps most importantly, people in pre-industrial societies rarely worked for wages in the way we understand them today. Instead, they participated in complex networks of barter, reciprocity, and mutual aid that bound communities together. If a farmer needed help building a barn, neighbors would contribute labor with the understanding that the favor would be returned when they needed assistance. If someone had a surplus of grain but needed pottery, they would trade directly with a local craftsperson.

This system created what economists call a “moral economy” – one where economic relationships were embedded in social relationships and community obligations. People had multiple roles and skills rather than narrow specializations. A farmer might also be a part-time carpenter, blacksmith, or weaver, depending on community needs and seasonal demands. Women typically managed household production, which included not just cooking and childcare, but also brewing, preserving food, making clothing, and often contributing to agricultural work.

The concept of “unemployment” simply didn’t exist in this world. As long as people had access to land and were part of a community, they could contribute to their own subsistence and that of their neighbors. There was no sharp distinction between “work time” and “life time” – productive activity was woven into the fabric of daily existence.

The Seeds of Change: Proto-Industrialization

The transition to our modern job-based economy didn’t happen overnight. Beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries, what historians call “proto-industrialization” began to emerge in parts of Europe. Rural families started producing goods not just for their own use, but for distant markets. A farming family might spend winter months spinning thread or weaving cloth that merchants would collect and sell in towns and cities.

This system, known as the “putting-out” or “domestic” system, represented a crucial intermediate step. Families still lived on their own land and maintained their agricultural activities, but they were increasingly integrated into market relationships. They began working for wages, but the work was still done in their own homes, at their own pace, integrated with other household activities.

The Industrial Revolution: The Birth of the Modern Job

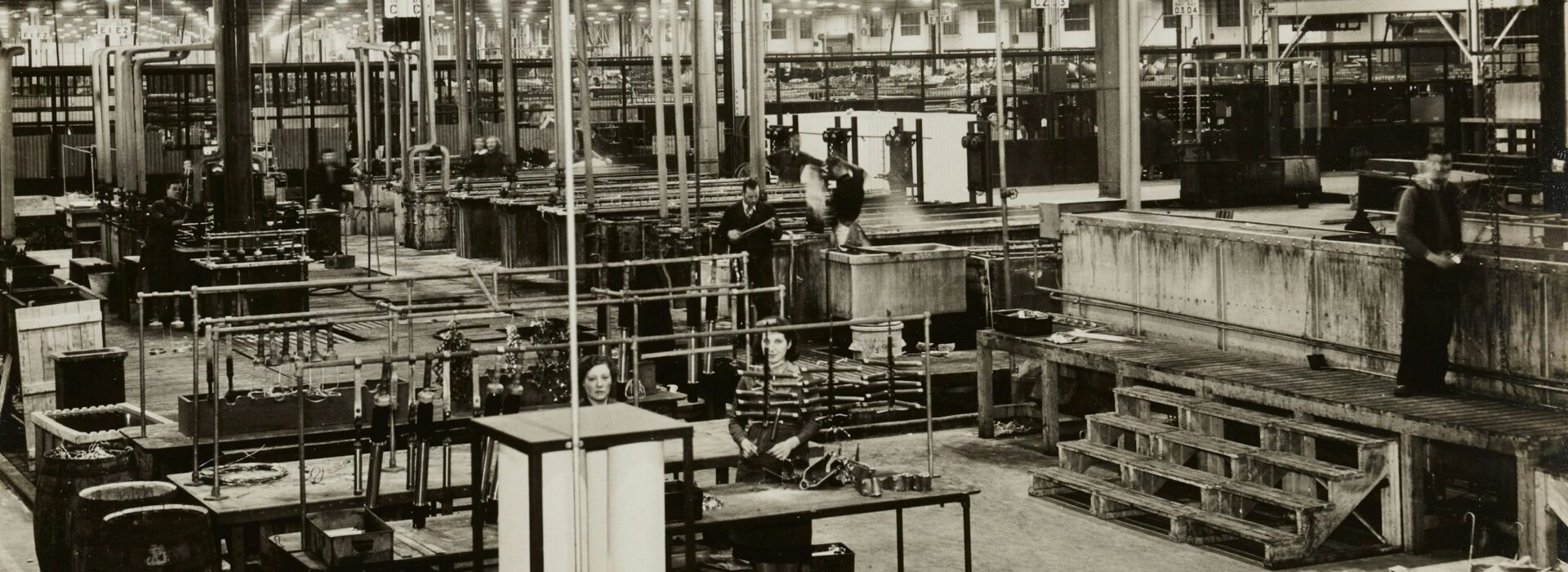

The true transformation came with the Industrial Revolution, beginning in Britain in the late 1700s and spreading across Europe and North America throughout the 1800s. Several interconnected changes combined to create the modern concept of employment as we know it.

First, new technologies – particularly steam power and mechanized production – made it profitable to concentrate workers in factories rather than having them work at home. These machines were too expensive for individual families to own and required coordination among workers to operate efficiently.

Second, the enclosure movement in Britain and similar processes elsewhere consolidated small farms into larger estates, forcing many rural families off the land they had worked for generations. Suddenly, millions of people found themselves without access to the means of subsistence that had sustained their ancestors for centuries.

Third, the rise of capitalism created a new class of entrepreneurs with the capital to build factories and the incentive to organize production for profit rather than subsistence. These factory owners needed workers who would show up at specific times, perform specific tasks, and accept wages in exchange for their labor.

The Transformation of Time and Work

Perhaps the most profound change brought by industrialization was the transformation of how people experienced time and work. In agricultural societies, work had followed natural rhythms – you worked when crops needed attention, when weather permitted, when daylight was available. The industrial factory demanded something entirely different: standardized time, regular schedules, and disciplined labor.

Factory whistles began to divide the day into precise segments. Workers had to arrive at a specific time, work for a predetermined number of hours, and leave when told to do so. This represented a fundamental break with centuries of human experience. For the first time in history, large numbers of people were selling their time rather than the products of their labor.

The specialization of industrial work also meant that most workers were now performing narrow, repetitive tasks rather than the varied work that had characterized pre-industrial life. A factory worker might spend their entire day operating a single machine or performing one step in a complex production process, never seeing the finished product of their labor.

The Social Revolution: From Communities to Markets

The rise of wage labor fundamentally altered social relationships as well. In pre-industrial communities, economic relationships were personal and embedded in ongoing social connections. You traded with neighbors you knew, worked alongside family members, and participated in community networks of mutual support.

Industrial employment created impersonal market relationships. Workers sold their labor to employers they might barely know, for wages that fluctuated with market conditions. The security that had come from community membership and access to land was replaced by the uncertainty of employment that could be terminated at any time.

This transformation created entirely new social problems. Unemployment became a distinct possibility – and a social crisis – for the first time in human history. Workers who had once been embedded in self-sufficient communities found themselves dependent on wages for survival, vulnerable to economic downturns, technological changes, and the decisions of distant employers.

The Persistence and Evolution of the Job Concept

Despite the dramatic changes that have occurred since the early Industrial Revolution – the rise of service industries, the growth of professional work, technological advances, and globalization – the basic structure of employment established in those early factories remains remarkably persistent.

Most of us still exchange our time for wages, work at locations and times determined by employers, and specialize in narrow tasks that contribute to larger production processes we may barely understand. We still face the fundamental uncertainty that comes from depending on employment rather than owning our own means of subsistence.

Understanding Our Economic Inheritance

Recognizing that the modern job is a historical invention rather than a natural feature of human life opens up important questions about our economic future. The current disruptions caused by automation, artificial intelligence, and changing work patterns are forcing us to reconsider assumptions about employment that have seemed natural for over two centuries.

As we face questions about universal basic income, the gig economy, remote work, and the future of jobs in an automated world, it’s worth remembering that the way we currently organize work and economic life is not inevitable or eternal. It emerged from specific historical circumstances, and it can be changed by human choices and social movements.

The concept of the job, born in the Industrial Revolution, has shaped our lives. But as we stand at another technological and social turning point, we have the opportunity to consciously shape what comes next, rather than simply accepting the economic arrangements we’ve inherited from the past.